Hree Main Art Styles Combined in Various Ways During the Italian Gothicproto Renaissance

Insular fine art, too known as Hiberno-Saxon art, was produced in the post-Roman era of the British Isles. The term derives from insula, the Latin term for "isle"; in this menstruation Britain and Ireland shared a largely common fashion different from that of the rest of Europe. Art historians commonly group insular art every bit part of the Migration Catamenia art movement equally well equally Early Medieval Western art, and it is the combination of these two traditions that gives the way its special character.[2]

Most Insular art originates from the Irish monastic movement of Celtic Christianity, or metalwork for the secular elite, and the period begins around 600 with the combining of Celtic and Anglo-Saxon styles. One major distinctive feature is interlace ornamentation, in particular the interlace decoration as establish at Sutton Hoo, in East Anglia. This is now applied to decorating new types of objects mostly copied from the Mediterranean world, above all the codex or volume.[3]

The finest period of the style was brought to an end by the disruption to monastic centres and aristocratic life caused by the Viking raids which began in the late 8th century. These are presumed to accept interrupted work on the Volume of Kells, and no later Gospel books are as heavily or finely illuminated as the masterpieces of the 8th century.[four] In England the style merged into Anglo-Saxon fine art around 900, whilst in Ireland the style continued until the 12th century, when it merged into Romanesque art.[5] Ireland, Scotland and the kingdom of Northumbria in northern England are the most important centres, but examples were found besides in southern England, Wales[half-dozen] and in Continental Europe, especially Gaul (modern French republic), in centres founded by the Hiberno-Scottish mission and Anglo-Saxon missions. The influence of insular art afflicted all subsequent European medieval art, especially in the decorative elements of Romanesque and Gothic manuscripts.[7]

Surviving examples of Insular art are mainly illuminated manuscripts, metalwork and carvings in rock, especially stone crosses. Surfaces are highly busy with intricate patterning, with no effort to give an impression of depth, volume or recession. The best examples include the Book of Kells, Lindisfarne Gospels, Book of Durrow, brooches such as the Tara Brooch and the Ruthwell Cross. Carpet pages are a characteristic feature of Insular manuscripts, although historiated initials (an Insular invention), canon tables and figurative miniatures, especially Evangelist portraits, are also mutual.

Apply of the term [edit]

The term was derived from its use for Insular script, first cited by the OED in 1908,[8] and is also used for the grouping of Insular Celtic languages by linguists.[9] Initially used mainly to describe the mode of ornamentation of illuminated manuscripts, which are certainly the most numerous blazon of major surviving objects using the mode, it is now used more widely across all the arts. It has the advantage of recognising the unity of styles across Britain and Republic of ireland, while avoiding the use of the term British Isles, a sensitive topic in Republic of ireland, and as well circumventing arguments virtually the origins of the way, and the identify of creation of specific works, which were frequently tearing in the 20th century,[10] and may be reviving in the 21st.[eleven]

Some sources distinguish between a "wider menstruation between the 5th and 11th centuries, from the difference of the Romans to the ancestry of the Romanesque way" and a "more than specific phase from the sixth to 9th centuries, between the conversion to Christianity and the Viking settlements".[12] C. R. Dodwell, on the other hand, says that in Ireland "the Insular fashion continued almost unchallenged until the Anglo-Norman invasion of 1170; indeed examples of it occur even every bit late as the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries".[13]

Insular ornamentation [edit]

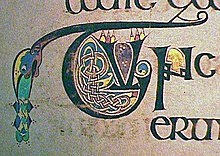

I of hundreds of minor initials from the Book of Kells

The Insular fashion is most famous for its highly dense, intricate and imaginative decoration, which takes elements from several earlier styles. Late Fe Historic period Celtic fine art or "Ultimate La Tène", gave the love of spirals, triskeles, circles and other geometric motifs. These were combined with animal forms probably mainly deriving from the Germanic version of the general Eurasian animal style, though as well from Celtic art, where heads terminating scrolls were common. Interlace was used by both these traditions, too as Roman fine art (for instance in floor mosaics) and other possible influences such equally Coptic art, and its use was taken to new levels in insular fine art, where it was combined with the other elements already mentioned.

There is no attempt to represent depth in manuscript painting, with all the emphasis on a brilliantly patterned surface. In early works the human being effigy was shown in the aforementioned geometric fashion equally animal figures, just reflections of a classical figure manner spread every bit the period went on, probably more often than not from the southern Anglo-Saxon regions, though northern areas also had direct contacts with the Continent.[xiv] The origins of the overall format of the rug page have often been related to Roman flooring mosaics,[15] Coptic carpets and manuscript paintings,[16] without full general agreement being reached among scholars.

Groundwork [edit]

Early Anglo-Saxon shoulder-clasps from Sutton Hoo, early 7th century. Gold, garnet, and millefiori glass.

Unlike contemporary Byzantine art, and that of most major periods, insular fine art does non come from a guild where common stylistic influences were spread across a neat number of types of object in art, applied fine art and decorative fine art. Across all the islands lodge was finer entirely rural, buildings were rudimentary, and architecture has no Insular way. Although related objects in many more perishable media certainly existed and accept not survived, it is articulate that both religious and secular Insular patrons expected individual objects of dazzling virtuosity, that were all the more dazzling because of the lack of visual sophistication in the earth in which they were seen.[17]

Especially in Ireland, the clerical and secular elites were often very closely linked; some Irish gaelic abbacies were held for generations among a pocket-size kin-grouping.[18] Ireland was divided into very small "kingdoms", almost too many for historians to keep rail of, whilst in Britain there was a smaller number of generally larger kingdoms. Both the Celtic (Irish and Pictish) and Anglo-Saxon elites had long traditions of metalwork of the finest quality, much of information technology used for the personal adornment of both sexes of the elite. The Insular manner arises from the meeting of their 2 styles, Celtic and Anglo-Saxon animal mode, in a Christian context, and with some awareness of Late Antique way. This was especially and then in their application to the book, which was a new type of object for both traditions, as well as to metalwork.[19]

The function of the Kingdom of Northumbria in the formation of the new style appears to have been pivotal. The northernmost Anglo-Saxon kingdom continued to expand into areas with Celtic populations, but oftentimes leaving those populations largely intact in areas such as Dál Riata, Elmet and the Kingdom of Strathclyde. The Irish monastery at Iona was established by Saint Columba (Colum Cille) in 563, when Iona was role of a Dál Riata that included territory in both Ireland and modern Scotland. Although the first conversion of a Northumbrian male monarch, that of Edwin in 627, was effected by clergy from the Gregorian Mission to Kent, it was the Celtic Christianity of Iona that was initially more influential in Northumbria, founding Lindisfarne on the eastern coast as a satellite in 635. Nevertheless Northumbria remained in direct contact with Rome and other of import monastic centres were founded by Wilfrid and Benedict Biscop who looked to Rome, and at the Synod of Whitby information technology was the Roman practices that were upheld, while the Iona contingent walked out, not adopting the Roman Easter dating until 715.[20]

What had finally settled into a broad consensus as to the origins of the style may be disturbed by the standing cess of the big numbers of decorated metalwork finds in the Staffordshire Hoard, found in 2009, and to a lesser extent the Prittlewell princely burial from Essex, found in 2003.[21]

Insular metalwork [edit]

The Hunterston Brooch, Irish gaelic c. 700, is bandage in argent, mounted with gold, silver and amber decoration.

Christianity discouraged the burial of grave goods so that, at least from the Anglo-Saxons, we accept a larger number of pre-Christian survivals than those from later periods.[22] The majority of examples that survive from the Christian menstruation have been constitute in archaeological contexts that suggest they were speedily hidden, lost or abandoned. There are a few exceptions, notably arm-shaped reliquaries such every bit the Shrine of Saint Lachtin's Arm,[23] and portable book-shaped ("cumdachs") and house-shaped[24] shrines for books or relics, several of which have been continuously endemic, generally by churches on the Continent—though the Monymusk Reliquary has ever been in Scotland.[25]

In general it is articulate that nearly survivals are merely by chance, and that nosotros have only fragments of some types of object—in detail the largest and to the lowest degree portable. The highest quality survivals are either secular jewellery, the largest and most elaborate pieces probably for male wearers, or tableware or altarware in what were apparently very like styles—some pieces cannot be confidently assigned between chantry and royal dining-table. It seems possible, even likely, that the finest church building pieces were fabricated by secular workshops, often fastened to a royal household, though other pieces were fabricated past monastic workshops.[26] The prove suggests that Irish metalworkers produced most of the best pieces,[27] withal the finds from the majestic burying at Sutton Hoo, from the far east of England and at the beginning of the period, are as fine in pattern and workmanship every bit any Irish gaelic pieces.[28] Even excepting the existence of workshops in the mid-to-late medieval period, the craftsman may non always take had been responsible for the full design of the works, for instance the execution of portions of the Ardagh Chalice evidence a lack of skill compared to the rest of the slice.[29]

There are a number of large penannular brooches, including several of comparable quality to the Tara brooch. Well-nigh all of these are in the British Museum, the National Museum of Republic of ireland, the National Museum of Scotland, or local museums in the islands. Each of their designs is wholly private in particular, and the workmanship is varied in technique and superb in quality. Many elements of the designs can be straight related to elements used in manuscripts. Almost all of the many techniques known in metalwork tin exist plant in Insular work. Surviving stones used in ornament are semi-precious ones, with amber and stone crystal amidst the commonest, and some garnets. Coloured glass, enamel and millefiori glass, probably imported, are as well used, every bit seen in the late 6th century Ballinderry Brooch.[30]

The golden-bronze Rinnegan Crucifixion Plaque (NMI, late seventh or early eighth century) is the all-time known of a group of nine recorded Irish metal Crucifixion plaques and is comparable in way to figures on many high crosses; it may well have come from a volume comprehend or formed role of a larger altar frontal or high cross.[31] [32]

The Ardagh Chalice and the Derrynaflan Hoard of chalice, paten with stand up, strainer, and basin (only discovered in 1980) are the nigh outstanding pieces of church metalware to survive (simply three other chalices, and no other paten, survive). These pieces are thought to come from the 8th or 9th century, merely well-nigh dating of metalwork is uncertain, and comes largely from comparison with manuscripts. Simply fragments remain from what were probably large pieces of church furniture, probably with metalwork on wooden frameworks, such as shrines, crosses and other items.[33] The Insular crozier had a distinctive shape; the survivals, such aas the Kells Crozier and Lismore Crozier all appear to be Irish or Scottish and from rather late in the Insular menstruation. These after works, which besides including the 11th century River Laune and Clonmacnoise Croziers are heavily influenced by Viking art and accept interlace patterns in the Ringerike or Viking art#Urnes-styles.[34] [35]

The Cross of Cong is a twelfth-century Irish processional cross and reliquary that shows insular ornament, possibly added in a deliberately revivalist spirit.[36]

The fittings of a major abbey church building in the insular flow remain difficult to imagine; one thing that does seem clear is that the about fully decorated manuscripts were treated equally decorative objects for display rather than as books for written report. The most fully decorated of all, the Book of Kells, has several mistakes left uncorrected, the text headings necessary to make the Canon tables usable have not been added, and when it was stolen in 1006 for its encompass in precious metals, it was taken from the sacristy, not the library. The book was recovered, but non the cover, as too happened with the Book of Lindisfarne. None of the major insular manuscripts accept preserved their elaborate jewelled metallic covers, but we know from documentary evidence that these were as spectacular equally the few remaining continental examples.[37] The re-used metal back embrace of the Lindau Gospels (now in the Morgan Library, New York[38]) was made in southern Germany in the late eighth or early 9th century, under heavy insular influence, and is perhaps the all-time indication as to the advent of the original covers of the great insular manuscripts, although 1 gilded and garnet piece from the Anglo-Saxon Staffordshire Hoard, establish in 2009, may be the corner of a volume-cover. The Lindau design is dominated by a cross, but the whole surface of the cover is decorated, with interlace panels betwixt the artillery of the cantankerous. The cloisonné enamel shows Italian influence, and is not constitute in work from the Insular homelands, but the overall result is very like a carpet folio.[39]

Insular manuscripts [edit]

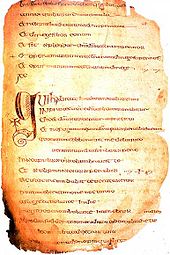

Cathach of St. Columba, 7th century

Cathach of St. Columba. An Irish Latin psalter of the early on 7th century,[twoscore] this is perhaps the oldest known Irish manuscript of whatever sort. It contains merely busy messages, at the beginning of each Psalm, but these already show distinctive traits. Not but the initial, but the first few messages are decorated, at diminishing sizes. The decoration influences the shape of the letters, and various decorative forms are mixed in a very unclassical manner. Lines are already inclined to spiral and metamorphose, as in the example shown. Apart from black, some orange ink is used for dotted decoration. The classical tradition was late to use capital letters for initials at all (in Roman texts it is often very hard to even carve up the words), and though past this time they were in common apply in Italian republic, they were oft set up in the left margin, as though to cut them off from the remainder of the text. The insular trend for the decoration to lunge into the text, and take over more and more of it, was a radical innovation.[41] The Bobbio Jerome which according to an inscription dates to before 622, from Bobbio Abbey, an Irish gaelic mission centre in northern Italy, has a more elaborate initial with colouring, showing Insular characteristics still more developed, even in such an outpost. From the aforementioned scriptorium and of like appointment, the Bobbio Orosius has the earliest rug page, although a relatively uncomplicated one.[42]

The first of the Gospel of Marker from the Book of Durrow.

Durham Gospel Volume Fragment. The primeval painted Insular manuscript to survive, produced in Lindisfarne c. 650, simply with only 7 leaves of the book remaining, not all with illuminations. This introduces interlace, and also uses Celtic motifs drawn from metalwork. The design of 2 of the surviving pages relates them equally a two-folio spread.[43]

Book of Durrow. The primeval surviving Gospel Book with a total programme of decoration (though not all has survived): six extant carpet pages, a total-folio miniature of the four evangelist's symbols, iv full-page miniatures of the evangelists' symbols, four pages with very big initials, and decorated text on other pages. Many minor initial groups are decorated. Its date and place of origin remain subjects of contend, with 650–690 and Durrow in Ireland, Iona or Lindisfarne existence the normal contenders. The influences on the ornamentation are as well highly controversial, especially regarding Coptic or other Near Eastern influence.[44]

Later large initials the following letters on the same line, or for some lines across, go on to be decorated at a smaller size. Dots round the outside of large initials are much used. The figures are highly stylised, and some pages use Germanic interlaced animal ornament, whilst others utilise the full repertoire of Celtic geometric spirals. Each page uses a unlike and coherent prepare of decorative motifs. Only four colours are used, simply the viewer is hardly witting of any limitation from this. All the elements of Insular manuscript style are already in place. The execution, though of loftier quality, is not every bit refined every bit in the best later books, nor is the scale of detail as small-scale.[45]

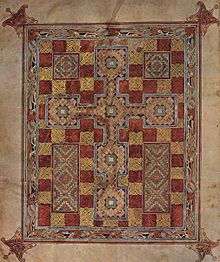

Carpet page from the Lindisfarne Gospels

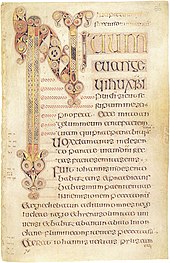

Lindisfarne Gospels Produced in Lindisfarne by Eadfrith, Bishop of Lindisfarne, betwixt about 690 and his death in 721 (perhaps towards the stop of this period), this is a Gospel Book in the manner of the Book of Durrow, simply more elaborate and complex. All the letters on the pages beginning the Gospels are highly decorated in a single composition, and many 2-page openings are designed every bit a unit, with carpet pages facing an incipit ("Here begins..") initial folio at the outset of each Gospel. Eadfrith was almost certainly the scribe as well as the artist. There are four Evangelist portraits, clearly derived from the classical tradition but treated without any sense of depth; the borders around them are far plainer than the ornament of the text pages, and there is conspicuously a sense of two styles which Eadfrith does not attempt to integrate wholly. The carpeting-pages are enormously circuitous, and superbly executed.[46]

Lichfield Gospels Probable made in Lichfield around 730, this deluxe gospel-book contains eight major decorated pages, including a stunning cross-carpet page and portraits of the evangelists Mark and Luke. The gospels of Matthew and Mark and the beginning of Luke survives. From its time in Wales, pages include marginalia representing some of the earliest examples of Old Welsh writing. The manuscript has been at Lichfield Cathedral since the late 10th century, except for a brief flow during the English Civil War.

St Petersburg Bede. Attributed to Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey in Northumbria betwixt about 730–746, this contains larger opening messages in which metalwork styles of decoration tin can conspicuously be seen. There are thin bands of interlace within the members of messages. It also contains the earliest historiated initial, a bust probably of Pope Gregory I, which like some other elements of the ornament, conspicuously derives from a Mediterranean model. Colour is used, although in a relatively restrained manner.[47]

Book of Kells Usually dated to around 800, although sometimes up to a century earlier, the identify of origin is disputed between Iona and Kells, or other locations.[48] It is likewise oft idea to take been begun in Iona and and then continued in Ireland, after disruption from Viking raids; the book survives most intact simply the decoration is non finished, with some parts in outline simply. It is far more than comprehensively decorated than any previous manuscript in any tradition, with every folio (except two) having many small decorated letters. Although in that location is only one carpeting page, the incipit initials are so densely decorated, with only a few letters on the page, that they rather accept over this office. Human being figures are more numerous than before, though treated in a thoroughly stylised manner, and closely surrounded, fifty-fifty hemmed in, by decoration as crowded as on the initial pages. A few scenes such equally the Temptation and Abort of Christ are included, besides as a Madonna and Child, surrounded by angels (the primeval Madonna in a Western volume). More than miniatures may take been planned or executed and lost. Colours are very bright and the decoration has tremendous energy, with spiral forms predominating. Gold and silver are not used.[49]

Other books [edit]

St John from the Book of Mulling

A distinctive Insular type of book is the pocket gospel book, inevitably much less decorated, only in several cases with Evangelist portraits and other ornament. Examples include the Book of Mulling, Volume of Deer, Book of Dimma, and the smallest of all, the Stonyhurst Gospel (now British Library), a 7th-century Anglo-Saxon text of the Gospel of John, which belonged to St Cuthbert and was buried with him. Its beautifully tooled goatskin cover is the oldest Western bookbinding to survive, and a almost unique case of insular leatherwork, in an excellent state of preservation.[50]

Both Anglo-Saxon and Irish gaelic manuscripts take a distinctive rougher finish to their vellum, compared to the smooth-polished surface of contemporary continental and all tardily-medieval vellum.[51] It appears that, in contrast to later periods, the scribes copying the text were often as well the artists of the illuminations, and might include the most senior figures of their monastery.[52]

Movement to Anglo-Saxon art [edit]

In England the pull of a Continental style operated from very early on; the Gregorian mission from Rome had brought the St Augustine Gospels and other manuscripts now lost with them, and other books were imported from the continent early on. The 8th-century Cotton fiber Bede shows mixed elements in the decoration, every bit does the Stockholm Codex Aureus of similar menstruum, probably written in Canterbury.[53] In the Vespasian Psalter it is articulate which element is coming to dominate. All these and other members of the "Tiberius" group of manuscripts were written s of the river Humber,[54] only the Codex Amiatinus, of before 716 from Jarrow, is written in a fine uncial script, and its but illustration is conceived in an Italianate style, with no insular decoration; it has been suggested this was but because the volume was made for presentation to the Pope.[55] The dating is partly known from the grant of additional land secured to raise the generations of cattle, amounting to ii,000 head in all, which were necessary to make the vellum for three complete simply unillustrated Bibles, which shows the resources necessary to make the large books of the period.

Many Anglo-Saxon manuscripts written in the south, and later the n, of England show strong Insular influences until the 10th century or beyond, but the pre-dominant stylistic impulse comes from the continent of Europe; carpet-pages are non found, simply many large figurative miniatures are. Panels of interlace and other Insular motifs proceed to be used as i element in borders and frames ultimately classical in derivation. Many continental manuscripts, especially in areas influenced by the Celtic missions, also show such features well into the early on Romanesque period. "Franco-Saxon" is a term for a school of tardily Carolingian illumination in north-eastern France that used insular-style decoration, including super-large initials, sometimes in combination with figurative images typical of contemporary French styles. The "most tenacious of all the Carolingian styles", it continued until as belatedly as the 11th century.[56]

Sculpture [edit]

Muiredach'due south High Cross, Monasterboice

Big stone high crosses, normally erected outside monasteries or churches, first announced in the eighth century in Ireland,[57] peradventure at Carndonagh, Donegal, a monastic site with Ionian foundations,[58] patently afterward than the primeval Anglo-Saxon crosses, which may be 7th-century.[59]

Later insular carvings found throughout Uk and Ireland were virtually entirely geometrical, every bit was the ornament on the earliest crosses. By the 9th century figures are carved, and the largest crosses have very many figures in scenes on all surfaces, often from the Erstwhile Testament on the east side, and the New on the west, with a Crucifixion at the center of the cross. The 10th-century Muiredach's High Cantankerous at Monasterboice is usually regarded as the peak of the Irish crosses. In later examples the figures go fewer and larger, and their style begins to merge with the Romanesque, equally at the Dysert Cross in Ireland.[sixty]

The 8th-century Northumbrian Ruthwell Cross, unfortunately damaged by Presbyterian iconoclasm, is the most impressive remaining Anglo-Saxon cross, though as with most Anglo-Saxon crosses the original cross head is missing. Many Anglo-Saxon crosses were much smaller and more than slender than the Irish ones, and therefore simply had room for carved leafage, but the Bewcastle Cross, Easby Cross and Sandbach Crosses are other survivals with considerable areas of figurative reliefs, with larger-scale figures than whatsoever early Irish examples. Fifty-fifty early Anglo-Saxon examples mix vine-scroll decoration of Continental origin with interlace panels, and in later ones the quondam type becomes the norm, just every bit in manuscripts. At that place is literary evidence for considerable numbers of carved stone crosses across the whole of England, and too straight shafts, often as grave-markers, but most survivals are in the northernmost counties. There are remains of other works of awe-inspiring sculpture in Anglo-Saxon art, fifty-fifty from the earlier periods, but nothing comparable from Ireland.[61]

Pictish continuing stones [edit]

The stone monuments erected by the Picts of Scotland north of the Clyde-Forth line betwixt the 6th–8th centuries are particularly hit in design and structure, carved in the typical Easter Ross manner related to that of insular art, though with much less classical influence. In detail the forms of animals are oft closely comparable to those institute in Insular manuscripts, where they typically represent the Evangelist's symbols, which may point a Pictish origin for these forms, or some other common source.[62] The carvings come from both pagan and early Christian periods, and the Pictish symbols, which are even so poorly understood, do not seem to take been repugnant to Christians. The purpose and meaning of the stones are only partially understood, although some think that they served equally personal memorials, the symbols indicating membership of clans, lineages, or kindreds and describe aboriginal ceremonies and rituals[63] Examples include the Eassie Rock and the Hilton of Cadboll Stone. Information technology is possible that they had subsidiary uses, such equally marking tribal or lineage territories. It has also been suggested that the symbols could have been some kind of pictographic organization of writing.[64]

At that place are also a few examples of like ornamentation on Pictish silvery jewellery, notably the Norrie's Law Hoard, of the seventh century or possibly before, much of which was melted downwardly on discovery,[65] and the 8th-century St Ninian'south Isle Hoard, with many brooches and bowls.[66] The surviving items from both are at present held past National Museums Scotland.[67]

Legacy of Insular art [edit]

The true legacy of insular art lies not and so much in the specific stylistic features discussed above, just in its fundamental deviation from the classical approach to decoration, whether of books or other works of art. The barely controllable energy of Insular decoration, spiralling across formal partitions, becomes a feature of later medieval fine art, particularly Gothic art, in areas where specific Insular motifs are inappreciably used, such as architecture. The mixing of the figurative with the ornamental too remained characteristic of all afterwards medieval illumination; indeed for the complexity and density of the mixture, Insular manuscripts are just rivalled by some 15th-century works of belatedly Flemish illumination. Information technology is likewise noticeable that these characteristics are e'er rather more pronounced in the n of Europe than the s; Italian art, even in the Gothic period, ever retains a certain classical clarity in form.[68]

Unmistakable Insular influence tin be seen in Carolingian manuscripts, even though these were also trying to copy the Imperial styles of Rome and Byzantium. Greatly enlarged initials, sometimes inhabited, were retained, as well as far more than abstruse decoration than found in classical models. These features continue in Ottonian and contemporary French illumination and metalwork, before the Romanesque flow further removed classical restraints, especially in manuscripts, and the capitals of columns.[69]

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Nordenfalk, 29, 86–87

- ^ Honour & Fleming, 244–247; Pächt, 65–66; Walies & Zoll, 27–30

- ^ No manuscripts are commonly dated earlier 600, but some jewellery, generally Irish, is dated to the sixth century. Youngs 20–22. The early history of Anglo-Saxon metalwork is dominated by the early-7th-century finds at Sutton Hoo, but information technology is clear these were the product of a well-established tradition of which only smaller pieces survive. Wilson, 16–27. The earliest Pictish stones may engagement from the 5th century however. Laing, 55–56.

- ^ Dodwell (1993), 85, 90; Wilson, 141

- ^ Ryan

- ^ The late Ricemarch Psalter is certainly Welsh in origin, and the much earlier Hereford Gospels is believed by many to be Welsh (see Grove Art Online, S2); the 10th-century Book of Deer, the primeval manuscript with Scottish Gaelic, is an Insular production of eastern Scotland (Grove).

- ^ Henderson, 63–71

- ^ OED "Insular" 4 b., though as it seems clear from their 1908 quotation that the apply of the term was already established; Carola Hicks dates the first employ to 1901.

- ^ Evidently a more recent usage from the ?1970s on, in works such as Cowgill, Warren (1975). "The origins of the Insular Celtic conjunct and absolute verbal endings". In H. Rix (ed.). Flexion und Wortbildung: Akten der 5. Fachtagung der Indogermanischen Gesellschaft, Regensburg, 9.–14. September 1973. Wiesbaden: Reichert. pp. 40–70. ISBN978-iii-920153-40-vii.

- ^ Schapiro, 225–241, Nordenfalk, eleven–14, Wailes & Zoll, 25–38, Wilson, 32–36, give accounts of some of these scholarly controversies; Oxford Art Online "Insular art", The Oxford Dictionary of Fine art Archived 5 September 2009 at the Wayback Auto

- ^ Hendersons

- ^ Hicks

- ^ Dodwell (1993), 90.

- ^ Grove, Wilson, 38–40, Nordenfalk, 13–26, Calkins Affiliate i, Laing 346–351

- ^ Henderson, 97–100

- ^ Nordenfalk, xix–22, Schapiro, 205–206

- ^ Henderson 48–55, Dodwell, nineteen and throughout Chapter 7

- ^ Youngs, 13–14

- ^ Youngs, 15–sixteen, 72; Nordenfalk, seven–11, Pächt, 65–66

- ^ Nordenfalk, eight–ix; Schapiro, 167–173

- ^ Hendersons

- ^ Dodwell (1982), iv

- ^ Mitchell (1984), p. 139

- ^ Moss (2014), 286

- ^ Youngs, 134–140 catalogues two examples from Italy and 1 from Norway. See likewise Laing, who describes major pieces past period and area at various points.

- ^ Youngs, 15–16, 125

- ^ Youngs, 53

- ^ Wilson, 16–25

- ^ Murray (2011), pp. 162, 164

- ^ Youngs, 72–115, and 170–174 on techniques; Ryan, Michael in Oxford Art Online, S2, Wilson, 113–114, 120–130

- ^ Johnson, Ruth. Irish gaelic Crucifixion Plaques: Viking Age or Romanesque?, The Journal of the Purple Society of Antiquaries of Republic of ireland, Vol. 128, (1998), pp. 95–106. JSTOR. Paradigm Archived 11 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ó Floinn; Wallace (2002), p. 187

- ^ Youngs, 125–130, and catalogue entries following, including the Derrynaflan Hoard.

- ^ Murray (2010), p. fifty

- ^ Ó Floinn; Wallace (2002), p. 220

- ^ Rigby, 562

- ^ Calkins 57–60. The 8th-century pocket gospel book Volume of Dimma has a fine 12th-century encompass.

- ^ "Gospel Book". themorgan.org. 13 July 2017. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Lasko, 8–ix, and plate 2; Lindau Gospels cover Archived 13 June 2010 at the Wayback Auto, from Morgan Library

- ^ Or "the 2d half of the sixth century" according to Schapiro, 229. Calkins, 31–32 gives no date, Nordenfalk, 12–13 says 7th century.

- ^ Pächt, 63–64, in his chapter on the initial, which gives a thorough handling of the subject. Nordenfalk, 12–13 has other images.

- ^ Schapiro, 227–229; Wilson, 60

- ^ Calkins, 32–33; Nordenfalk, 14–15, 28, 32–33

- ^ Calkins, 33–63 gives a total business relationship with many illustrations; Nordenfalk, 34–47, and nineteen–22 on Coptic influences; see also Schapiro Index (under Dublin), Wilson, 32–36 and alphabetize.

- ^ Calkins, 33–63 gives a full account with many illustrations; Nordenfalk, 34–47.

- ^ Calkins, 63–78; Nordenfalk, threescore–75

- ^ Schapiro, 199–224; Wilson, 63

- ^ Dodwell, 84

- ^ Calkins, 78–92; Nordenfalk, 108–125

- ^ Bloxham & Rose, and images Archived 25 Nov 2005 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Wilson, 32

- ^ Alexander, 9 and 72. The tradition that St Cuthbert copied the Stonyhurst Gospel himself may be correct, though that attributing the Book of Kells to St Columba himself seems incommunicable. For other loftier-ranking Anglo-Saxon monastic artists see Eadfrith of Lindisfarne, Spearhafoc and Dunstan, all bishops.

- ^ Nordenfalk, 96–107

- ^ Wilson, 91–94

- ^ Alexander, 72–73

- ^ Dodwell (1998), 74(quote)–75, and meet index.; Pächt, 72–73

- ^ Grove Fine art Online S4

- ^ Michael Herity, Studies in the layout, buildings and art in stone of early Irish gaelic monasteries, Pindar Press, 1995

- ^ Wilson, 54–56, 113–129

- ^ Grove

- ^ Wilson deals extensively with the sculptural remains, 74–84 for the 8th century, 105–108, 141–152, 195–210 for later on periods.

- ^ Laing, 54–55, Henderson, 59

- ^ Laing, 53–56. Run across also C. Michael Hogan, Eassie Stone, The Megalithic Portal, editor: Andy Burnham, 2007 Archived iv March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Forsyth, Katherine (1997), Henry, David (ed.), "Some thoughts on Pictish Symbols as a formal writing arrangement" (PDF), The Worm, the Germ and the Thorn. Pictish and related studies presented to Isabel Henderson, Balgavies, Forfar: Pinkfoot Press, pp. 85–98, ISBN978-1-874012-16-0, archived (PDF) from the original on 29 September 2011, retrieved 10 December 2010

- ^ Youngs, 26–27

- ^ Wilson, 117–118; Youngs, 108–112, see also Shetland museum images Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Auto

- ^ Master, Ian Brooks; Sven Border; Xabier Garcia; Jamie Wheeler; Andy. "Search Results". nms.scran.ac.united kingdom . Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Henderson, 63–71; A major theme of Pächt, see in detail affiliate Ii and pp. 173–177

- ^ Pächt, 72–73, and Henderson 63–71

Sources [edit]

- Alexander, Jonathan J.G.. Medieval Illuminators and their Methods of Work, Yale UP, 1992, ISBN 978-0-300-05689-1

- Bloxham, Jim & Rose, Krisine. St. Cuthbert Gospel of St. John, Formerly Known as the Stonyhurst Gospel

- Brown, Michelle P. Mercian Manuscripts? The "Tiberius" Group and its Historical Context, in Michelle P. Brown, Carol Ann Farr: Mercia: an Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2005, ISBN 978-0-8264-7765-ane

- Calkins, Robert G. Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1983, ISBN 978-0-8014-1506-7

- Dodwell, C.R. (1982). Anglo-Saxon Art, a new perspective, 1982, Manchester UP, ISBN 978-0-7190-0926-6

- Dodwell, C.R. (1993). The Pictorial arts of the Westward, 800–1200, 1993, Yale Upwards, ISBN 978-0-300-06493-3

- Gombrich, E.H. The Story of Art, Phaidon, 13th edn. 1982. ISBN 978-0-7148-1841-two

- Ó Floinn, Raghnal; Wallace, Patrick (eds). Treasures of the National Museum of Ireland: Irish Antiquities. Dublin: National Museum of Ireland, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7171-2829-7

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2012). Pages from the Book of Kells. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00AN4JVI0

- Grove Art Online. "Insular Art", accessed 18 April 2010, see likewise Ryan, Michael.

- Henderson, George. Early on Medieval Art, 1972, ISBN 978-0-xiv-021420-8, rev. 1977, Penguin,

- "Hendersons": Henderson, George and Henderson, Isabel, "The implications of the Staffordshire Hoard for the understanding of the origins and development of the Insular art fashion equally information technology appears in manuscripts and sculpture", Papers from the Staffordshire Hoard Symposium (online), 2010, Portable Antiquities Scheme, British Museum

- Hicks, Carola. Insular – The Age of Migrating Ideas: Early Medieval Art in Northern Britain and Ireland

- Hugh Honour and John Fleming. "A World History of Art", 1st edn. 1982 & later editions, Macmillan, London, folio refs to 1984 Macmillan 1st edn. paperback. ISBN 978-0-333-37185-5

- Laing, Lloyd Robert. The archeology of late Celtic Great britain and Republic of ireland, c. 400–1200 Advertizing, Taylor & Francis, 1975, ISBN 978-0-416-82360-8

- Lasko, Peter. Ars Sacra, 800–1200, Penguin History of Art (now Yale), 1972 (nb, 1st edn.) ISBN 978-0-fourteen-056036-7

- Moss, Rachel. Medieval c. 400—c. 1600, "Art and Compages of Ireland" series. CT: Yale Academy Printing, 2014. ISBN 978-03-001-7919-4

- Mitchell, G. F. "The Cap of St Lachtin'south Arm". The Journal of the Regal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, volume 114, 1984. JSTOR 25508863

- Moss, Rachel. The Book of Durrow. Dublin: Trinity College Library; London: Thames and Hudson, 2018. ISBN 978-0-5002-9460-four

- Murray, Griffin. "The Makers of Church Metalwork in Early Medieval Ireland: Their Identity and Status". Making Histories: Proceedings of the Sixth International Insular Art Conference. York, 2011

- Murray, Griffin. "The Medieval Treasures of County Kerry".Tralee: Kerry County Museum, 2010. ISBN 978-0-956-5714-0-three

- Nordenfalk, Carl. Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Painting: Book illumination in the British Isles 600–800. New York: George Braziller, 1976, ISBN 978-0-8076-0825-8

- Pächt, Otto. Book Illumination in the Center Ages (trans fr German), 1986, Harvey Miller Publishers, London, ISBN 978-0-19-921060-ii

- Rigby, Stephen Henry. A companion to Britain in the later Middle Ages, Wiley-Blackwell, 2003, ISBN 978-0-631-21785-v. Google books

- Ryan, Michael, and others, in Grove Art Online, Insular art (Ryan is also a major contributor to Youngs below)

- Schapiro, Meyer, Selected Papers, volume three, Late Antique, Early Christian and Mediaeval Fine art, 1980, Chatto & Windus, London, ISBN 978-0-7011-2514-1

- Wailes, Bernard and Zoll, Amy L., in Philip L. Kohl, Clare P. Fawcett, Nationalism, politics, and the practice of archæology, Cambridge University Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-521-55839-six

- Wilson, David M. Anglo-Saxon Art: From The Seventh Century To The Norman Conquest, Thames and Hudson (US edn. Overlook Press), 1984, ISBN 978-0-87951-976-half-dozen

- Susan Youngs (ed.). "The Work of Angels", Masterpieces of Celtic Metalwork, sixth–9th centuries Advert, 1989, British Museum Printing, London, ISBN 978-0-7141-0554-3

Further reading [edit]

- Treasures of Early Irish Art, 1500 B.C. to 1500 A.D.: From the Collections of the National Museum of Ireland, Purple Irish University, Trinity College, Dublin. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1977. ISBN9780870991646.

External links [edit]

- Book of Kells - images of manuscript

- Book of Mulling - images of manuscript

- "Lindisfarne Gospels" - images from the British Library

- Irish gaelic Brooches of the Early Medieval Celtic Menstruum - exhibition

- Lichfield Gospels - instructive Features page for the manuscript; interactive 3D renderings; interactive Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) for viewing dry-indicate; overlaid historical images (going dorsum 125 years) to examine how the manuscript is aging

- 3D for Presenting Insular Manuscripts - Explains 3D modeling for the 8th-century illuminated St Chad Gospels

Source: https://wikizero.com/www//Pocket_gospel

0 Response to "Hree Main Art Styles Combined in Various Ways During the Italian Gothicproto Renaissance"

Postar um comentário